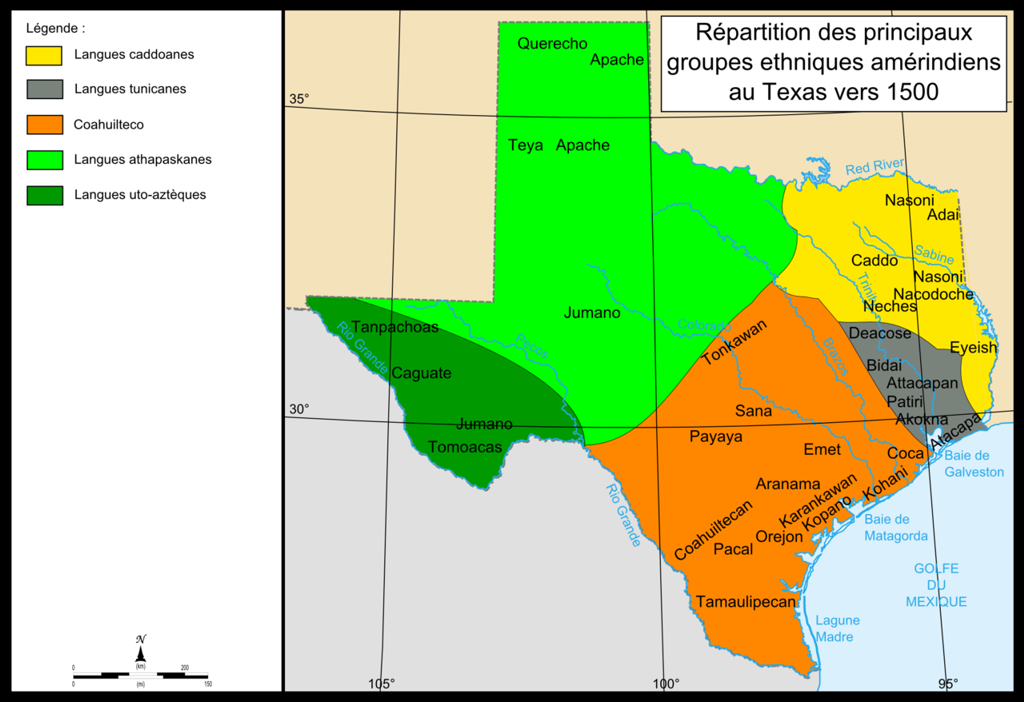

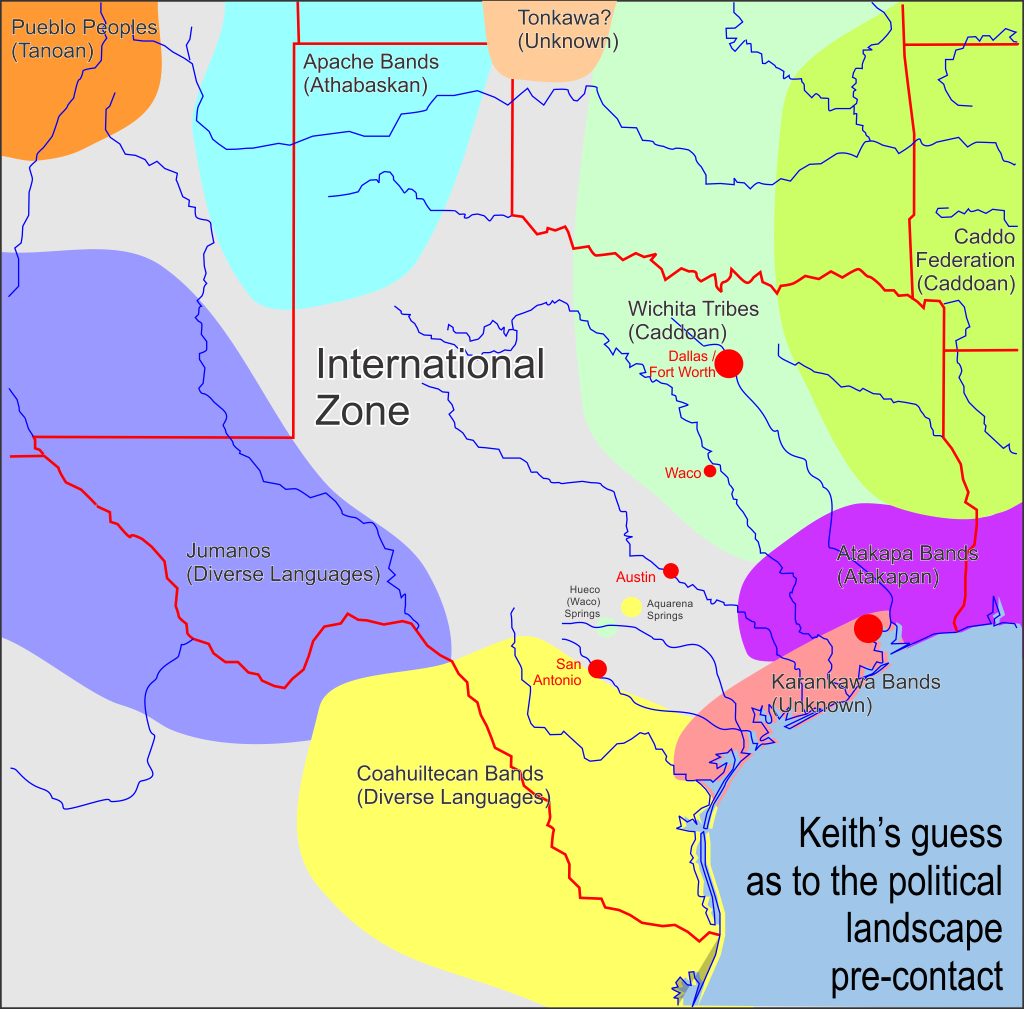

For some time now, I’ve felt an impending time pressure regarding the Texas Problem. After some very simple divination, I took the hour-and-a-half drive up to Waco to see if I could learn anything new about the situation there.

I resolved to visit Proctor Springs, a group of natural springs in Cameron Park. I suspect these were near the settlement known as El Quisciat, which was described as being on a bluff with springs somewhere in the vicinity of the later, larger “Waco” settlement.

The springs are in the older part of the park. There is a distinct feeling of visiting ancient ruins. A large number of crumbling concrete stairs, streams, pools, and paths criss-cross the area, often disconnected from the newer trails. Anniversary Hill Park in Holyoke, Massachusetts has a similar “ruins” feel to it.

I left offerings of roasted corn, dried fruit, and nuts at the two main spring seeps and some significant trees. I picked up a bunch of trash. Typical stuff. Aside from a vague sense of “generally healthy park”, I didn’t have any particular experiences of note near the springs.

The springs flow into a creek, which I followed upstream through Lindsey Hollow. Aside from some additional Fae markers, nothing. The markers I noticed didn’t strike me as particularly unusual for a well-established woodland- trees forming arches and the like. Nor did I feel any particular menace or concern. A little harmless misdirection, like driving right past the turn I needed to take, but nothing that felt sinister.

This part of Waco basically felt more like what I expect woodlands to feel like, i.e.- NOT affected by the Texas Problem. Even the best experiences I’ve had around Austin felt “cloaked” or “sandbagged” by comparison.

On the way to wash my hands (I forgot to bring trash gloves!), I finally noticed a structure that I’d passed twice already during the day:

Yes, immediately after crossing a creek at the old entrance of the park, the road forks. More than that, someone decided to build it out as a triple crossroads. Even more than that, someone did this:

That is a miniature colonnade, surrounding a large urn inside a circle. Perhaps the person(s) who built it didn’t really know what they were doing. Perhaps they did. Who knows? Either way, it might have taken me awhile to notice the shrine, but I certainly wasn’t going to ignore it now.

As soon as I washed my hands, I prayed and made an offering at the urn- to the vocal amusement of a pre-teen in a passing car. Whatever. You find an appropriate shrine where you weren’t expecting one, you pray at it.

It’s clear to me that the park is, as suspected, liminal.

What is less clear is whether the park is an Awakened landscape surrounded by a terribly mundane one; or, is it an exposed bit of REAL surrounded by hundreds of miles of dampening / glamour? I strongly suspect that the park is a place where the Texas Problem is very thin. So much so that I’m even wondering if it would be better to host Hearthingstone nearby instead of in Austin.

Probably not, but it might be good to at least have a working solution to the larger issue by the time it rolls around.

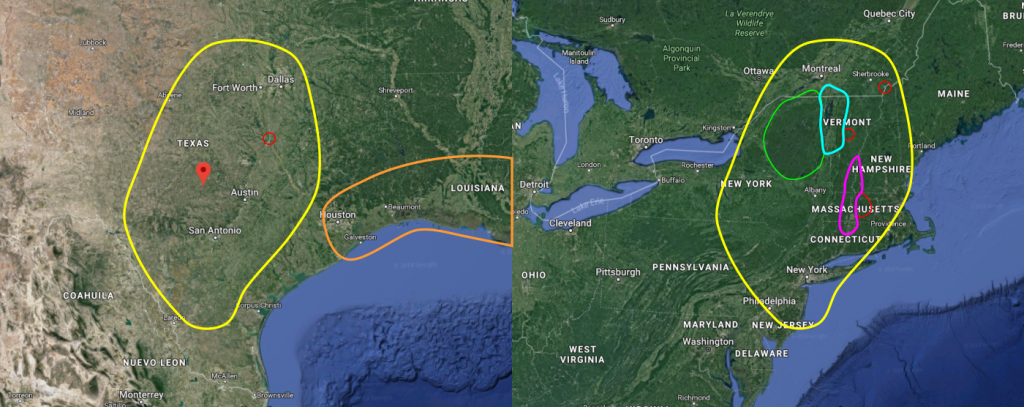

By this point, I was already pretty exhausted and dehydrated, having (for safety reasons) resolved to eat and drink only things from outside of Waco. Before I left, however, I did want to locate a mysteriously recondite historical marker- the Waco Village site.

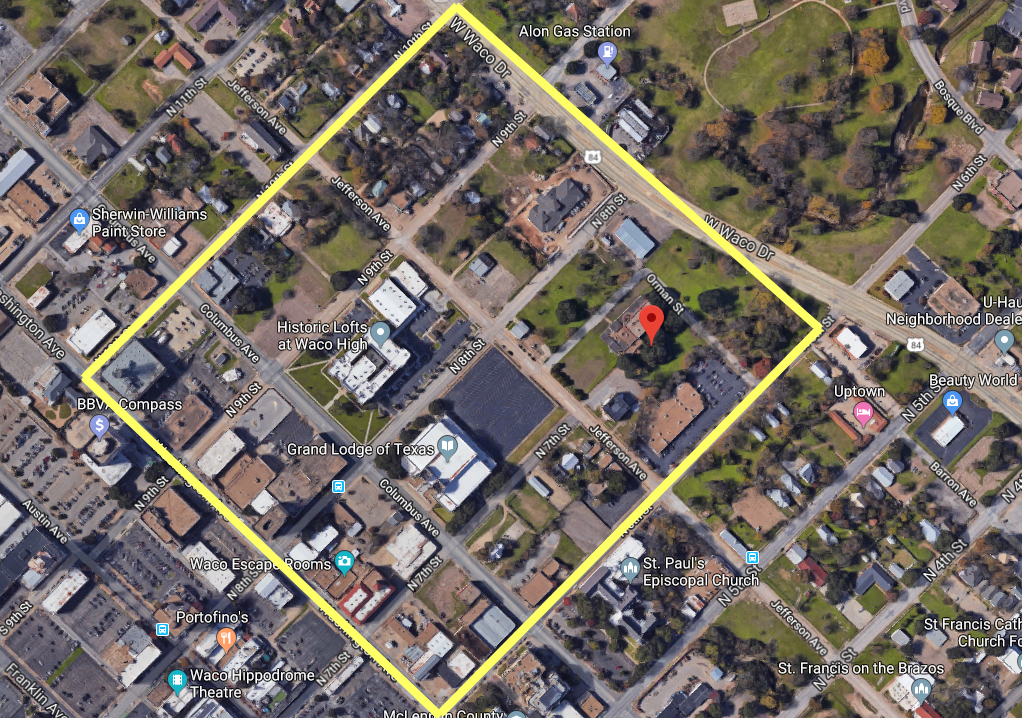

Officially, the marker is located at 701 Jefferson Avenue. A quick Google Street View reveals nothing of the kind, though. I eventually figured out that it is under an immense tree next to the Taylor Museum, which appears to be all but closed.

Obviously, the language of the marker is suspect, but it does provide at least a possible location. Adjacent to the marker and the museum is an African-American Baptist church. Across the street is the Grand Lodge of Texas- the central Masonic temple for Texas. I don’t know whether they consciously built it right there- but as with the shrine at the park, it might not be simple coincidence.

The city block in the lower center is (very roughly) about 2 acres in size. If reports from the early 1800s are accurate, the Waco village was about 40 acres in size and surrounded by an earthwork. The yellow square shows a vague approximation of what 40 acres looks like in modern Waco.

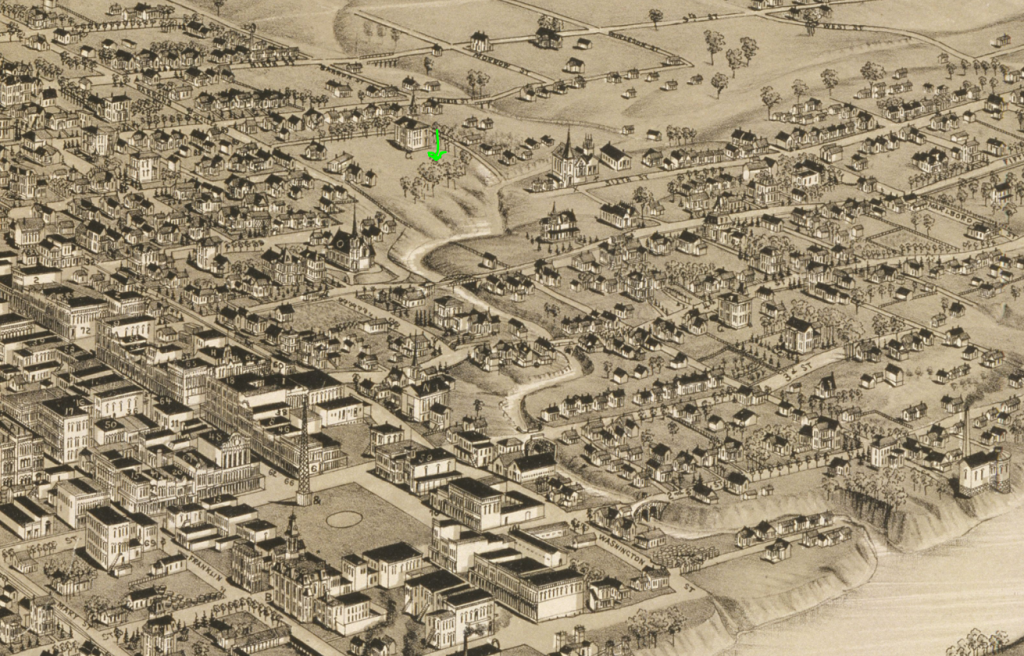

If we transpose this location to the 1886 map, we can see that the site overlooks a creek that is largely invisible in modern Waco except for the mouth, which is undergoing some kind of construction. Notice that this location also appears to be on a bit of a bluff. It’s possible that El Quisciat might have been there all along, but I doubt it. I think the “bluff” in question would’ve been taller and closer to the river.

Anyway, I don’t yet have any really good answers, but hopefully something I gained from the trip will be useful in the future. If I’ve learned something actionable, I haven’t grokked it yet.

-In Deos Confidimus