There is a pretty popular video game named Death Stranding that centers around the concept of tying places together via a “Chiral Network” that routes information through the Otherworld. While the game is fiction, the core esoteric concept is not.

Starting in the early 2010s, a good chunk of my landwork involved “spirit bridges”. These are point-to-point connections constructed using an exchange of materials, usually stone.

Originally, my spirit bridges were tiny, no more than a few hundred yards- usually much less. The rationale was to permit spiritlife to move more freely around their environment, unhampered by humanmade obstacles.

For example, connecting two sides of a road for the benefit of very small entities who previously had unfettered access to each other. The idea is analogous to “wildlife crossings“- tunnels or bridges erected to help biological wildlife move from place to place.

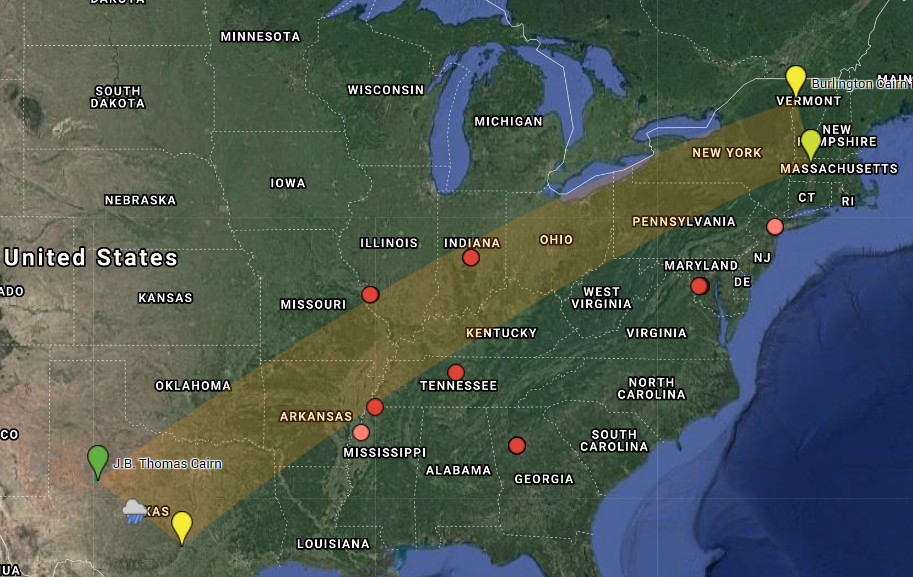

Then, in 2012, a friend and I set out to address a blockage in Vermont that was inhibiting the attempts of healthy spiritlife from the Lake Champlain watershed to help heal some of “The Sick” that was infecting the Connecticut River watershed.

While the physical crossing was small, and should have been easy to bridge, the entire area was under the control of a hostile, unidentified Power that drove us off. Clearly said Being did not want the traffic running through Their territory and was likely the cause of the break in the first place. While I’m now fairly certain of the Entity’s identity, there wasn’t much I could do about His decisions.

This led me to start working on longer-range spirit bridges, ones that were more complicated to erect and maintain. These were built on the same esoteric foundations, but would be consecrated to and mediated by Holy Powers for safety reasons.

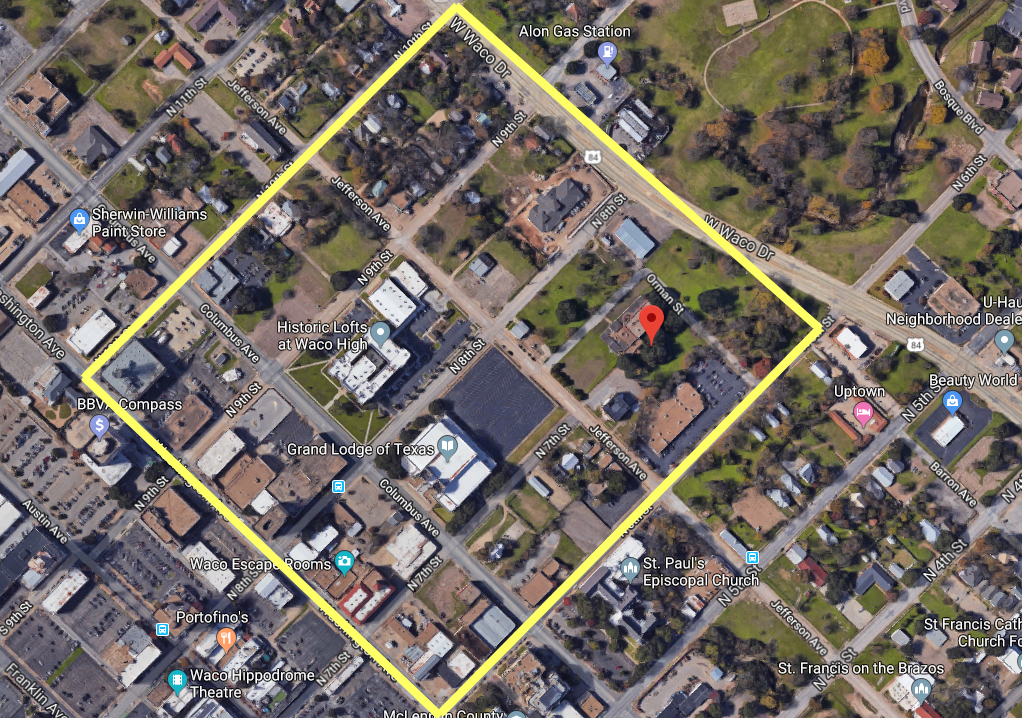

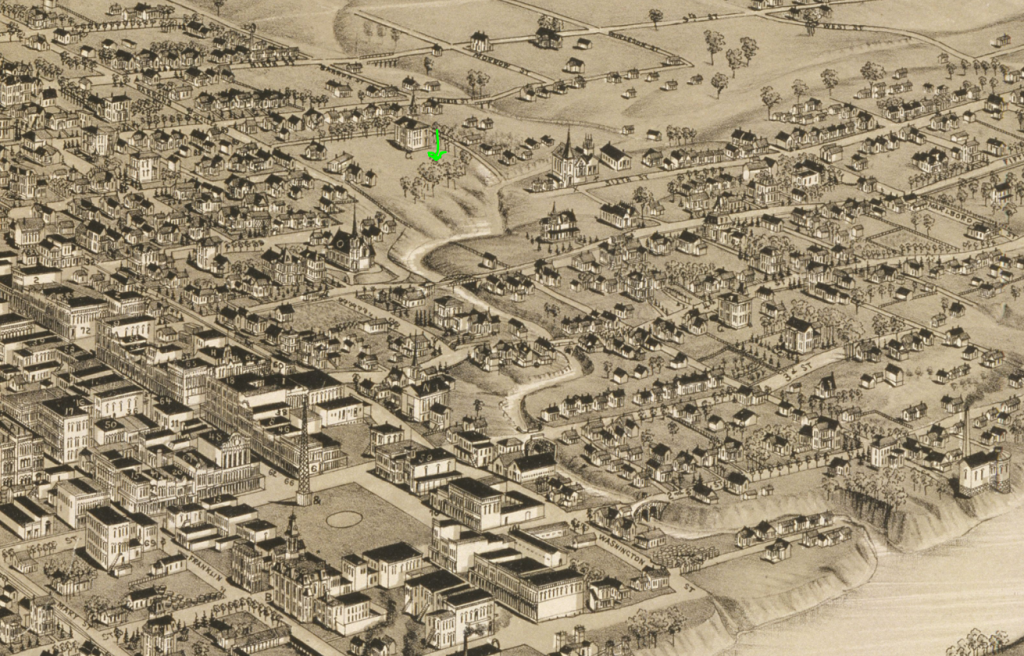

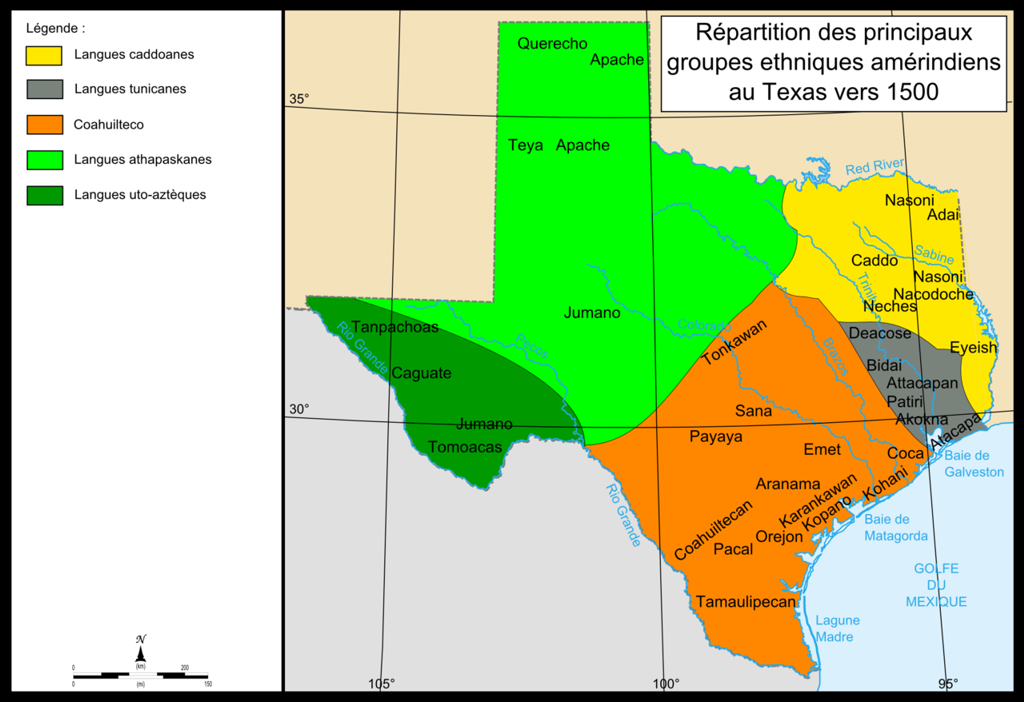

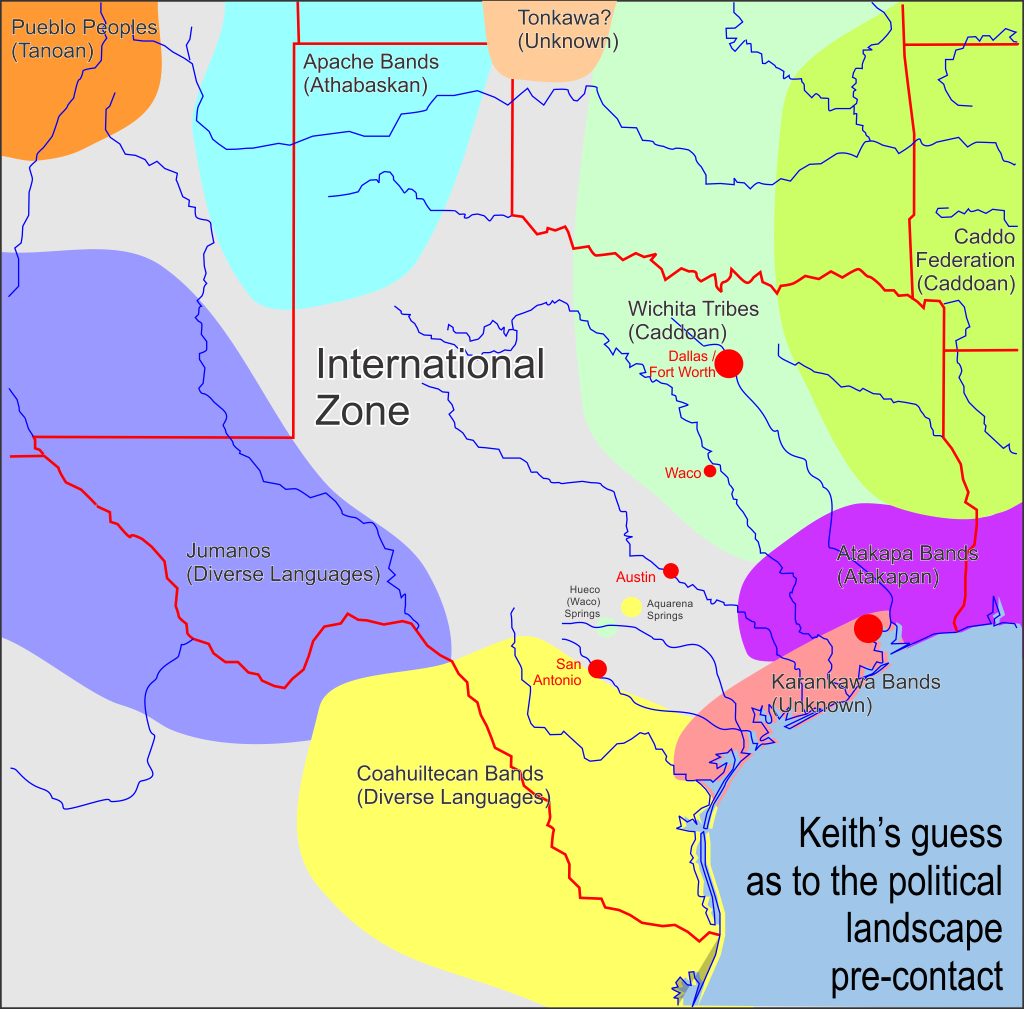

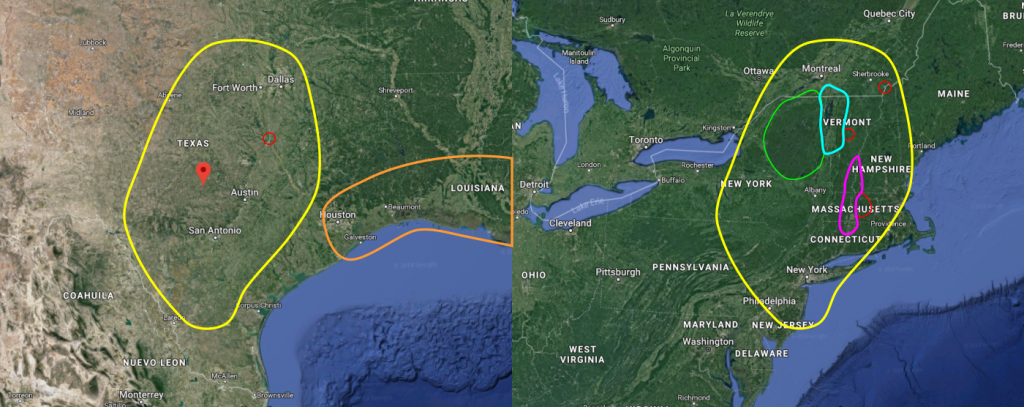

Between 2013 and 2014, I erected four spirit bridge cairns:

By the end of 2015, between life stresses, vandals, and just plain entropy the strain of maintaining just the Austin cairn by myself became too much. I convinced myself that the system wasn’t actually working and stopped.

At the end of 2015, Hideo Kojima began work on Death Stranding.

Do I think certain Gods made Kojima make this game so I’d realize the system wasn’t a failure?

No.

But I am more and more convinced that Someone(s) wove meaning into it, something Holy Powers have been doing for centuries. And I don’t think I’m the sole target audience.

Remember, one of the big problems that led me to abandon the Spirit Bridges Program (ooh, now it sounds important!) was the strain of doing it myself. This is in part my own shortcomings. I’ve always been a solo operative and struggle to involve others in my work. However, part of it was also an operational security fear.

As mentioned elsewhere, landwork has been both a tool of conquest and of resistance. Being more open about the spirit bridge technology meant increasing the risk of sabotage. It also increased the potential that it could be hijacked by faiths hostile to our attempts to heal our environment and restore right relations with our spiritlife neighbors.

On the sabotage front, I was clearly overly concerned with secrecy. In vain it turns out, since the Austin cairn kept getting destroyed even without anyone knowing what it was. Had I assistance with maintaining it, perhaps it would still be there. Instead, afraid of sabotage, I tried to do it all myself and it wound up destroyed anyway.

Of course, the esoteric connection is still there, but it’s much weaker without regular maintenance.

While the plot of Death Stranding focuses on expanding the Chiral Network (technobabble spirit bridges), the actual “core loop” involves strengthening interpersonal connections. This is done explicitly- as you help people, they give you more access to resources, and the like. However, it is also implicit in the game- the more you connect, the more you see evidence of other players in the game world.

For instance, the first time you pass through an area, you might see a ladder or a rope left behind by another player that helps you climb a cliff. The second time, you might see more ladders and a postbox. Each time you cross a section of map you might see more and more features, bridges, charging stations, watchtowers… All of these are structures built by other players to make it easier for them (and you) to traverse the map.

You never see the other players, only their work.

I suspect that this was the point that certain Gods were trying to get across by nudging Kojima’s team throughout the making of Death Stranding:

We are not alone. There are others doing the work.

And we need to connect.

– In Deos Confidimus