I made it to Hamilton Pool yesterday.

Aside from a stone I’d planned to offer disappearing in under a minute, I can’t report any clearly supernatural anything.

Which is par for the course.

I’d hoped the cold weather and overcast would thin the tourism. It might have, but I was still sharing the area with 100 people or so. Many of them chattering away like humans should not in such places.

The photo above shows a panorama, but of course the aspect ratio is a bit weird. You have to imagine the far left and right edges almost meeting behind you.

Two dominant features of the site are a waterfall near the left side of the opening and a moss-covered area near the right. There is a wavering line of drips from above that forms an arc between the two.

I say dominant because after walking all around the site, those were the two places that most drew my attention. The Texas Problem was still in evidence here. Though intellectually I could tell this was a place of power, between the other humans and the “cloak” I was barely picking up much of anything.

The first couple of hours was spent meditating in different spots, trying to do basic centering and grounding. This was a bit easier here than in the city, but not by much because there were still so many humans making disruptive noises.

I had fasted since the night before, not long, but enough to feel the drag of it. My hope was that it would sharpen my focus, which sometimes it does. I’m not sure if it helped, hindered, or neither.

After slowly making circumnavigating from the waterfall side to the beach (washed out in the center of the picture), I decided that the mossy area and the waterfall were the focal points where I needed to make offerings.

While the tourists thinned out, I sat on the beach and used a tiny rock with sharp edges as a burin to etch a horned serpent into a small cobble.

Once all but 30 or so tourists had departed, I made my way from the beach to the mossy area. From certain angles, it bears a resemblance to a large, sunken skull overgrown with moss. It also appeared to host a spring or seep that was coming from deeper than the water falling from above.

Still dodging tourists and park rangers (they often try to interrupt offerings), I first presented tobacco:

I offer you this tobacco, in honor and gratitude.

Then I offered a handful of toasted corn:

I offer you this corn, in honor and gratitude. Thank you for allowing me to visit this place.

Then, I had more people show up from out of nowhere, so I got flustered as I was packing up the corn. Somewhere around this point, I lost track of the etched rock. I may have left it on a post nearby or stuck it in my backpack and lost it in there.

I next moved clockwise around the inner section of the grotto, stopping periodically to meditate again. At one point, I noticed that the drips from above formed a pretty clear horned serpent motif- but only from that angle.

From another angle, I noticed several very faint, sinuous ripples on the surface, like invisible snakes 40′ long or more with their heads in the waterfall and their tails very slowly swishing back and forth to maintain position. I had not noticed them from that same vantage point earlier.

The waterfall was also flowing stronger than earlier for no reason I could discern. It was not raining in the area, nor anywhere upstream that I was aware of.

By this point, I was down to less than a dozen tourists, and I clambered down to the base of the waterfall. There, a massive red stone, like a huge egg some ten or twenty feet across, emerges from the pool and is drummed upon by one branch of the waterfall.

Here I readied four offerings:

- The rest of my tobacco.

- More toasted corn.

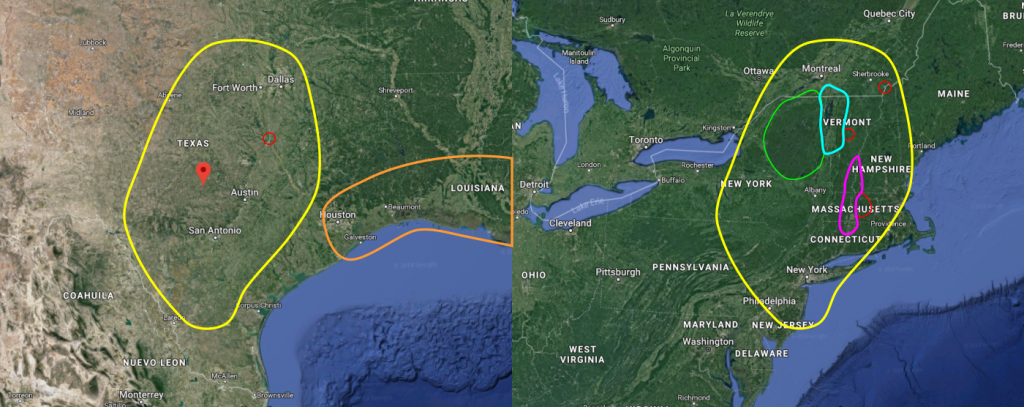

- A red stone from Lake Champlain, triangular in shape and flat.

- A smaller stone from a cenote in New Mexico, which I set atop the red stone.

These I carefully arranged on a flat-topped boulder nearby.

I turned, stood directly next to the waterfall with my hands and arms wide and invoked my hosts.

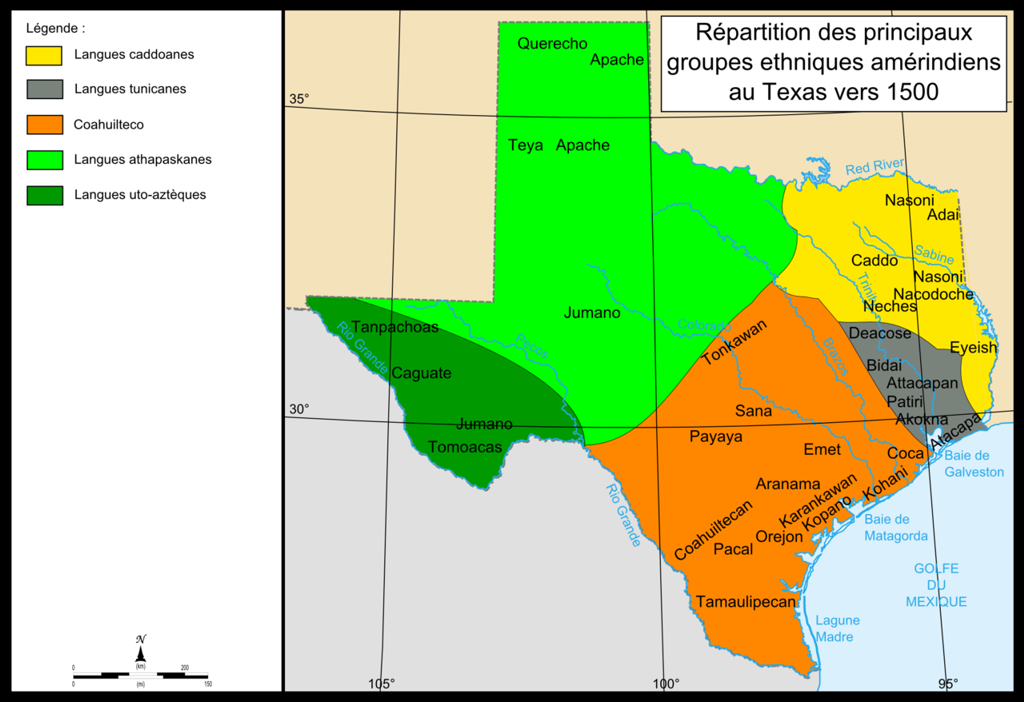

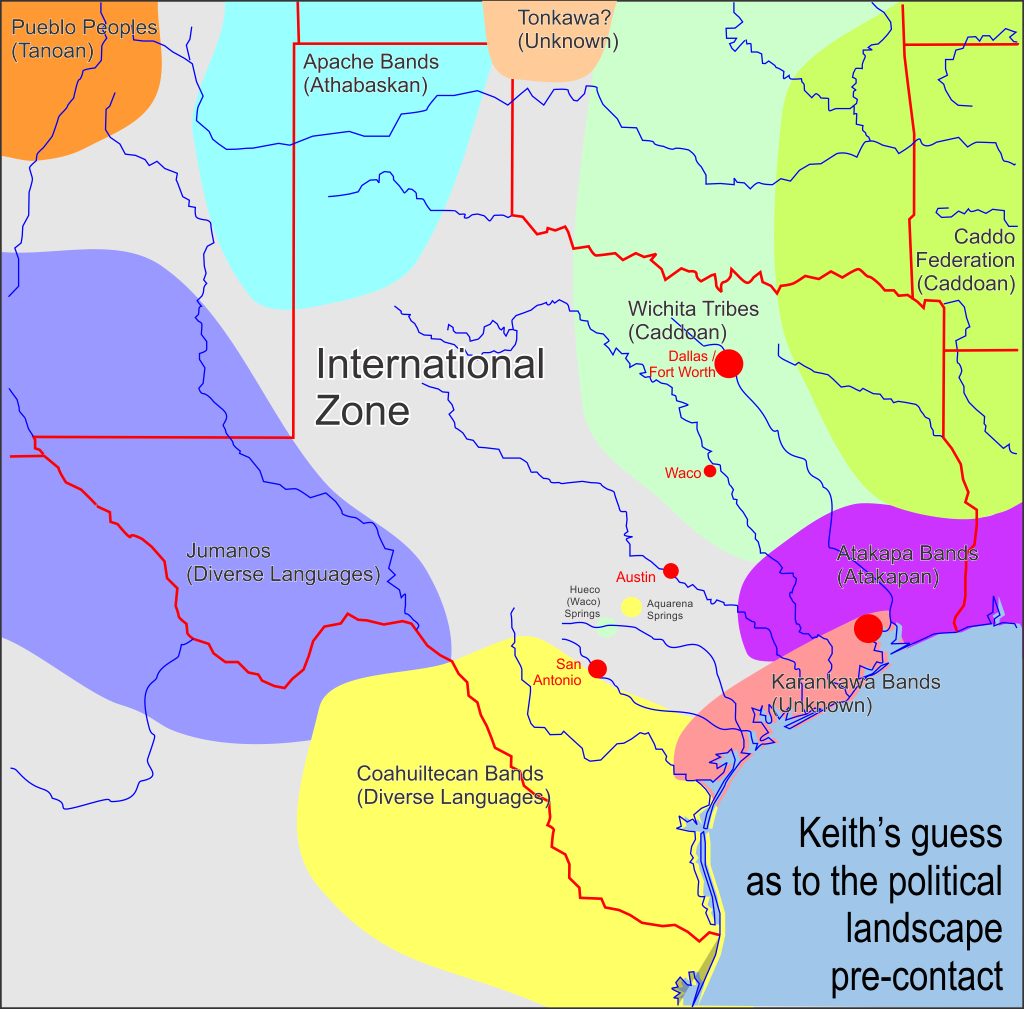

O, Great Serpents of Central Texas- you who dwell in this sacred place, your kindred, your ancestors, and all of your kind who call this region home…

While I was primarily trying to get the attention of the immediate locals, I wanted to make sure I was indicating an attempt to show respect to and communicate with the large “body politic”- for lack of a better term.

I am Keith, son of Michael, son of Eugene, of the line of Cormac.

This bit served multiple purposes:

- Firstly, placing me in a context of lineage not only asks my own ancestors for help, but gives my hosts something longer-lasting than me to wrap their minds around. As humans, our individual lives are short compared to much of the spiritlife we are dealing with.

- Secondly, the overly formal recitation establishes gravitas and that my purpose for being there was diplomatic, not simply a friendly “how-do-you-do” visit.

- Thirdly, that last bit is significant in its own right. While the “Cormac” in question is not necessarily Cormac mac Airt (probably isn’t), the name establishes a longer ancestral tie back to Europe and invites said blood ancestor(s) and said High King of Ireland emeritus to step in if they want to.

It’s worth noting that none of the genders are important. The wording feels right to me, but others may want to name their lineage differently or by tradition instead of blood relations. The important thing is to outline a lineage of strength.

I come to you humbly and to apologize. My people have not been respectful of you, nor of the land. Most of my people’s ancestors came from across the sea to the east. We live here now.

Once, my people knew better- they knew how to show respect and to live with the inhabitants of the land. But they were deceived by a new god, who led them astray, who blinded them to you. I wish to help my people learn again.

I turned back to the boulder, took up the tobacco, and placed it with both hands into the waterfall.

I offer you this tobacco, in honor of you and in gratitude.

I turned back to get the corn, and its lid had blown off (I’d loosened it already). The cenote stone was also gone.

Just… Gone.

I took up as much corn as I could hold, and with both hands placed it in the waterfall.

I offer you this corn, in honor of you and in gratitude.

I turned back to look for the cenote stone, which weighed about half a pound (not a pebble). It wasn’t on the ground around the boulder, and it certainly wasn’t atop the several-pound red stone, where I’d left it!

I took up the red stone instead and with both hands placed it atop the large red stone at the base of the waterfall.

I offer you this red stone from Lake Champlain, the land of Odzihozo, that you might have this as a connection to Him and to his land. I also brought a stone from a cenote in New Mexico, for the same reason, but now I cannot find it. I hope that you already have it.

I stepped back, now sopping wet despite my duster and wide-brimmed hat.

I ask that you help my people to see you, to hear you, to recognize you, to learn respect for you. Help them understand what their ancestors once knew. Let them see the land as it is, as it should be, that they may be good neighbors to you and to the land.

I waited.

I thank you for allowing me to come here and for listening.

Sensing no particular response, I packed my things and began huffing and puffing my way back up the trail from the floor of the canyon. I stopped at one point to offer the rest of the corn to the other inhabitants of the area after eating two pieces to demonstrate that it was safe.

I also picked up some trash here and there while exploring and on the way back. There wasn’t much- the rangers do a really good job policing rubbish.

Once back in my car, I thanked Hermes and Hekate for guiding me in and out of that liminal zone.

Then I ate the meat stick and candy bar I’d left in the car for post-working food. If you’re not in the habit of setting food and drink aside ahead of time, you should be. It’s a good safety precaution.

That’s about it.

So far, no further indications of anything.

-In Deos Confidimus