Tomorrow, I’m heading to Hamilton Pool to at least begin an attempt to “do the thing“. For some time now, I’ve been aware of the principle that a people’s sovereignty, in the landwork sense, is typically associated with a particularly important pool of water- a “sacred well“.

Specifically, there is some kind of a meeting at this location between a representative of the people and a powerful entity or deity who controls the region. What happens during that meeting varies wildly- depending on the mythology in question, the specific individuals involved, and the reporter. The events run the gamut from sacred marriages to chaoskampf-style battles to the death.

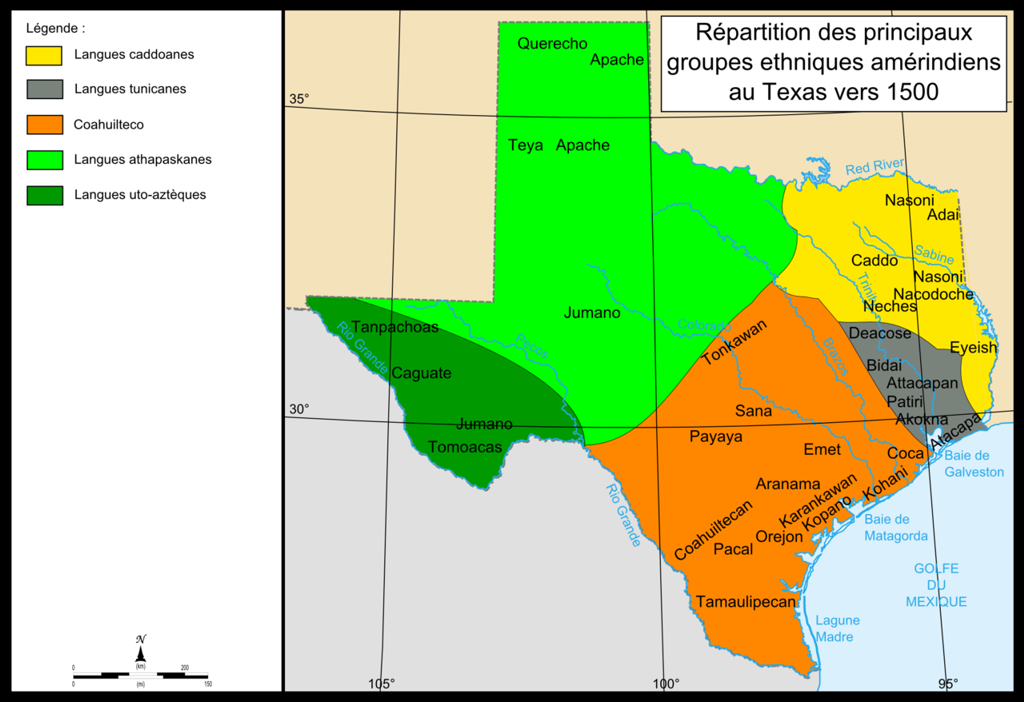

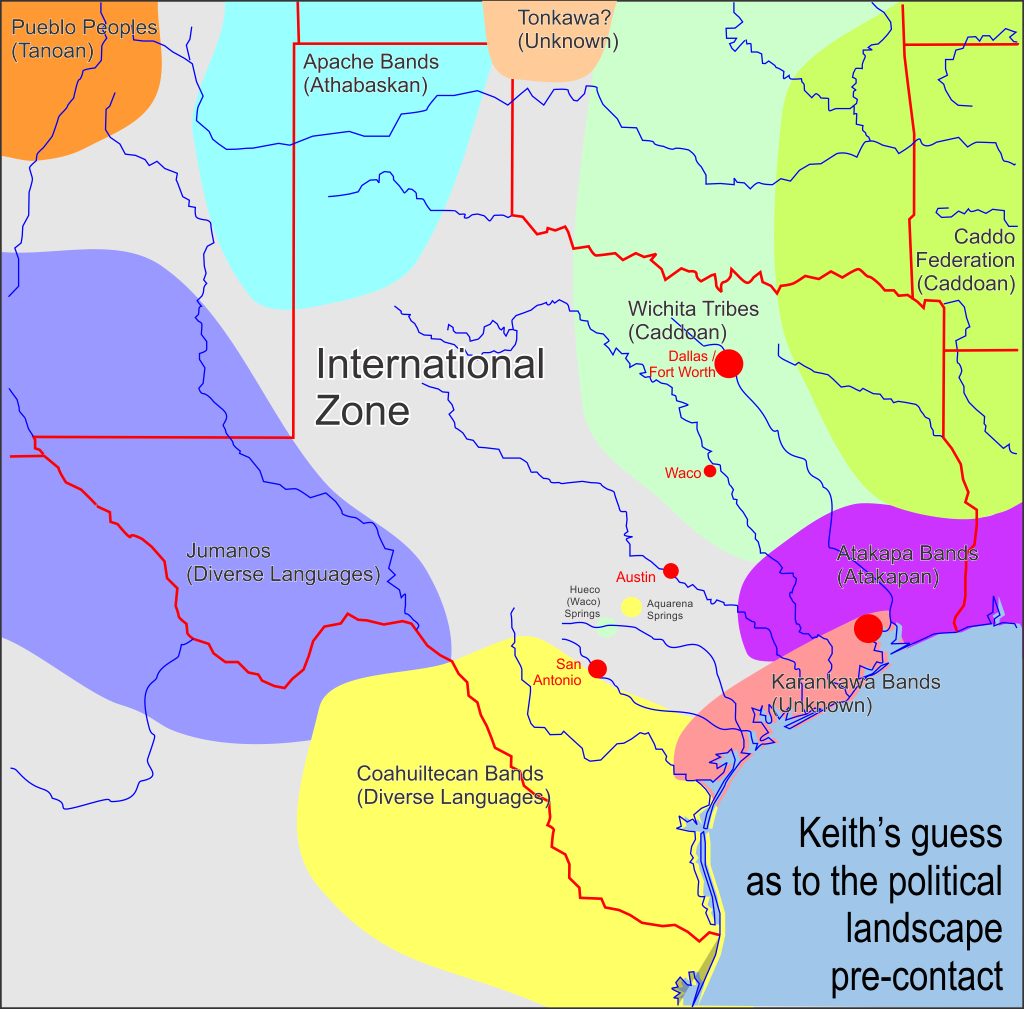

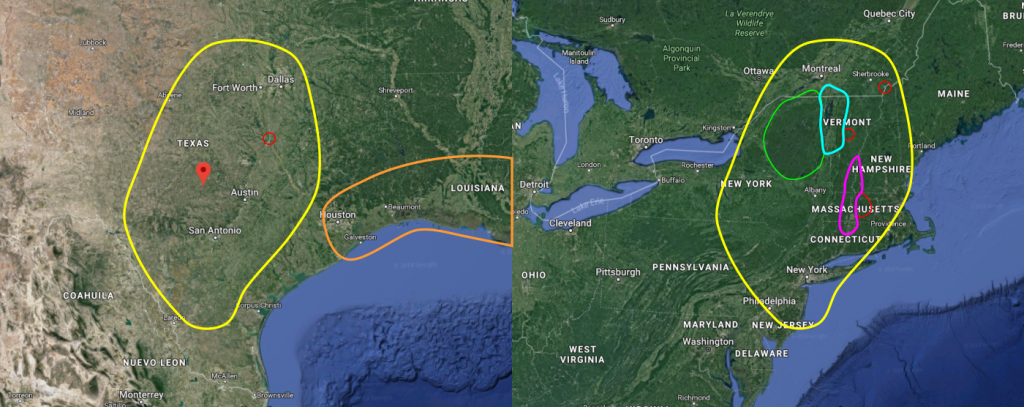

I’ve spent a great deal of time trying to figure out where this “well” was for Central Texas, and I kept coming back to Hamilton Pool. To be fair, most landscapes have lots of smaller sites that might be associated with a homestead, hearthing, or village. There are lots of important springs in Central Texas to be sure- such as Aquarena Springs, sacred to a number of bands of the Coahuiltecan peoples.

I’m after the big one- the one that links the smaller sites in the affected region.

In Central America and up into parts of the desert Southwest, the most important water holes are often cenotes.

Here in Central Texas, many of the smaller springs are along the edge of the Balcones Fault, which runs roughly parallel to Interstate-35. Hamilton Pool is upstream of nearly all of them.

Damn. I just rediscovered a site directly next to Hamilton Pool (Westcave) that I may need to visit as well. It’s also a cenote, or as they like to call it, a grotto.

Note that grottoes were common sacred sites in the Old World as well. Many of Apollo’s oracular sanctuaries were built near or around spring-fed caverns. Delphi, in particular, was the home of Python, a great serpent slain by Apollo in one of those chaoskampf events I mentioned earlier.

Why are cenotes or grottoes so important? Aside from their mysterious ability to remain full of clean water even during long droughts, they are almost universally recognized as liminal places. Typically they connect the human world with the underworld, which in many mythologies is also the source of all water.

Here in the Americas this is a common belief, but we find it in many parts of the world. Some Hindus and Buddhists, for instance, hold that all of the world’s freshwater springs originate in Patala, the underworld home of the Nagas.

In the Dindsenchas, the River Boyne is said to be the source of all the world’s great rivers and to have been created when Boann angered a vitally important sacred well which was home to dreadful magic.

Back to Greece, Heracles fought the Lernaean Hydra in a region of springs. Lake Lerna itself was associated with the cleansing of miasma and was an entrance to the underworld (Hades).

In Japan, Susano’o slew a great serpent or water dragon at the headwaters of a river. From its tail, He drew the sacred sword which was later handed down via the imperial line.

In Scandinavia and even into England, lindworms and knuckers were often associated with waterways, wells, and caverns.

There are plenty of non-serpents associated with sacred waters, but the serpents show up a LOT, especially in regard to the sites of greatest importance.

The Americas are no exception as far as dangerous giant serpents associated with waterways, cenotes, and grottoes.

A recurrent motif, the horned or plumed serpent, appears throughout much of the New World. The Lakota tell of Unhcegila and Unk Tehi, who rose out of the Atlantic and crossed half the continent spreading blindness, insanity, flooding, and death until they were stopped by one or more brave heroes or by Thunderbirds.

The Cherokee have Uktena, while the Abenaki know Pita-Skog. The Ojibwe have Mishi-ginebig and the Menominee speak of Misikinubik. In Central America we have Kukulkan and Quetzalcoatl, though They tend to bridge not only underworld and human world but also the overworld/sky as well.

So to with Avanyu of the Tewa peoples of the desert Southwest, most especially the Rio Grande Valley.

In some cases, these entities are considered deities, whereas in other traditions they are simply inhabitants of great power. The legends differ on humans’ ability to deal diplomatically with these powerful beings.

I honestly don’t know what to expect tomorrow, now later today. In all likelihood, I won’t notice anything going on. Indeed, I fear that as failure. On the other hand, Hamilton Pool has a long history of mysterious drownings- and Westcave won’t even allow people to their cenote without guides.

As far as offerings, roasted corn and tobacco might be traditional, but I don’t know for sure. Certain of these beings appear to accept these offerings just fine. On the other hand, because tobacco could be considered aerial if burnt, it might be offensive to the purely chthonic sort, even in a non-burning form.

I guess we’ll find out.

-In Deos Confidimus